If you walk into the public entrance of the Library of Congress expecting to gain access to the Main Reading Room, you will be sadly disappointed. The main entrance is for tourists and exhibits, and if you just want to sit and write in the reading room assisted by free federal wifi you first need to create the universe — or at least go to an altogether different building to get a card, a Library-of-Congress Card, with your photo and signature like a driver’s license, but for books.

The nice woman at the information desk will explain this to you and say that you can leave the Jefferson Building and walk (in the cold, clammy December air) to the Madison Building, across Independence Avenue, or, she will say, slightly conspiratorially, because maybe she has recognized a certain adventurousness in you — or at least a reluctance to go breathe in more of the humid chill outdoors — that there are tunnels that connect the buildings. Yes, you will say, your face shining with sudden interest, I would like to take the tunnels.

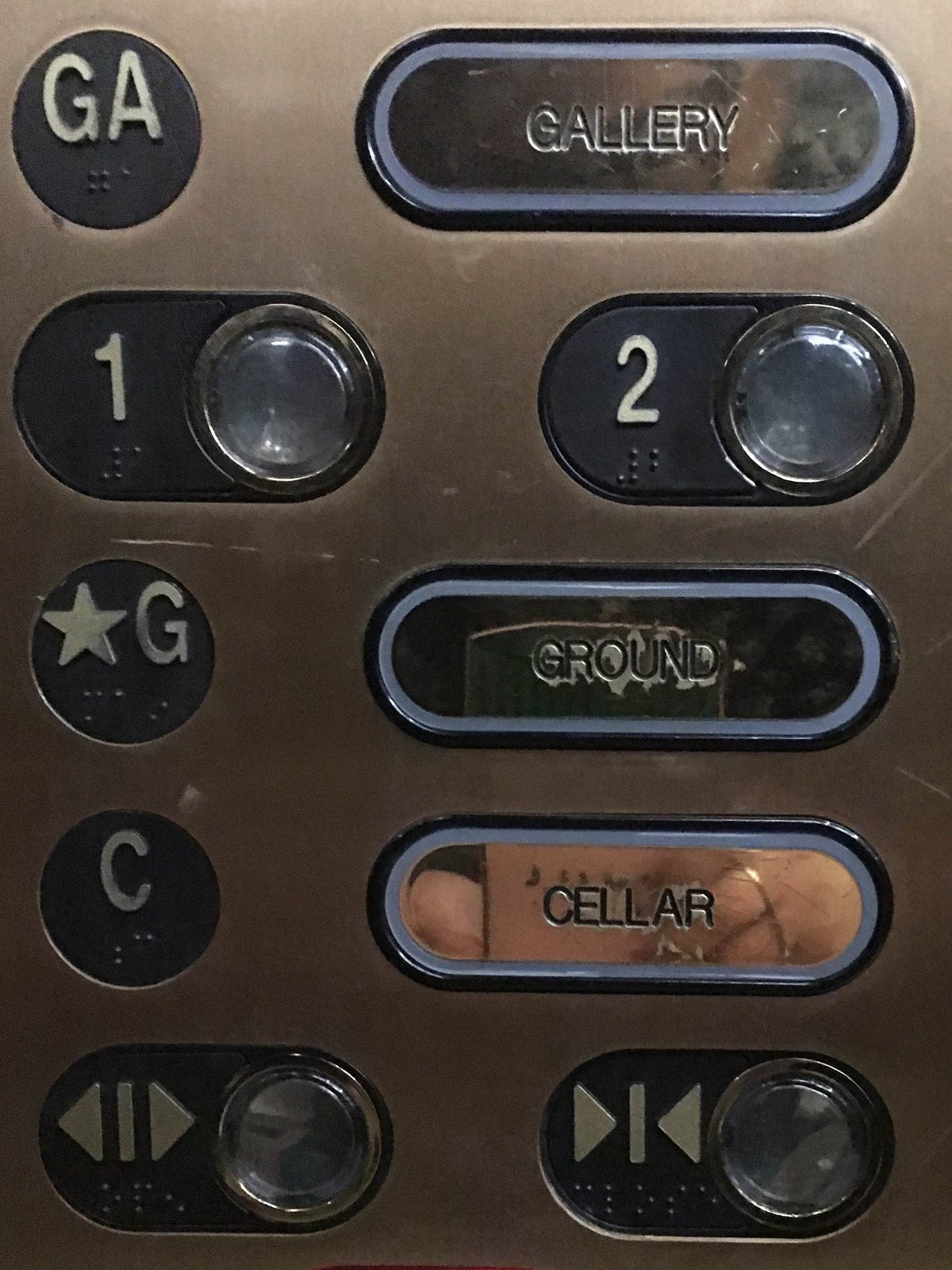

She will direct you to an elevator nestled in a corner of the large exhibit hall where three guided tours are all happening simultaneously and tell you to press the button for “cellar” (“CELLAR!” you will think joyfully) and when the doors open to follow the signs for the Madison building.

At first you will walk through a zigzagging corridor with extraordinary numbers of brightly colored wires bundled together on the ceiling, and then you will move into long white corridors decorated with gathered bouquets of long white pipes. There are other people down here and they all look very unlike you, many of them in blue shirts that mark them as employees, while you walk with sharp attention, peering around at every detail like a tourist and smiling at every employee you pass, most of whom will silently nod and smile back.

You will see the passage of book trains, these rolling sets of shelves clasped together like railway cars and pulled by a small whirring electric engine, its yellow lights flashing, driven by another man in a blue shirt. Some trains are stopped on one side of the corridor awaiting their locomotive; as you pass these you slow your gait to look at their titles, but they are set with their LOC classification numbers facing up and despite the halfhearted year you spent in a Library Science master’s degree program you don’t remember enough about that system to guess what these books are about.

As you continue to walk into the basement (CELLAR!) of the Madison Building you find there is an underground Dunkin Donuts and an underground Subway sandwich joint but as hungry as you are you keep going until you find the reader registration office, where you show your ID to two people and fill out a brief online form and then have your picture taken (twice, because “your hair was sticking up” and “yes, it usually is”) by a woman with less patience or warmth than the average DMV employee. You walk out with a Reader Card which will now gain you admission to the Reading Room after you stop at the secret underground Dunkin Donuts where clots of Librarians of Congress and other government employees are spending the morning drinking hot beverages and chatting with no apparent pressure to be anywhere else. Thus fortified, you will walk back to the Jefferson Building via the same tunnels, noticing new details, like that there are carpentry and masonry shops down there, carpentry and masonry for the Library.

These are some of the things you cannot bring into the Main Reading Room at the Library of Congress: newspapers, food, pets coats scissors photocopiers (not handheld) televisions typewriters umbrellas or musical instruments. Also bags, even the sleeve for your laptop. You will inquire again of a different helpful information desk employee how one gains physical entrance to the Main Reading Room once one has gone through the process of procuring one’s Reader Card, and she will produce a paper map and draw a line for you down the hall you need to go and where to check your coat in the cloakroom before you go in, along with lots of other things that need to be checked in the cloakroom. This will be the third paper map on which someone has helpfully drawn your route today.

At the cloakroom you will ask the attendant, “What can I take in with me and what do I have to leave?” She will say, “You have to leave your coat and your bags but you can take everything else in with you.” Because all you have is your coat and your bags it takes you a moment to grasp that what she means is that you need to take everything out of your bags that you want and carry it in your hands to the Reading Room, one floor up. You haphazardly remove your wallet and a notebook and a pencil and your laptop and a mouse you probably won’t need and your phone and your asthma inhaler and some lip balm and you foolishly decide against bringing the cough drops you’re carrying around against the cold you’re getting over and this will prove to be an error later. You also leave behind all three paper maps with their helpful lines of progress and later hope you won’t need one to find your way back, but even if you did, you could probably find someone else to draw on a map for you. The cloakroom attendant, who is polite and patient in spite of wanting to get back to her telephone conversation and game of what you think is Bejeweled, is very kind and even offers you a clear plastic bag to collect your odd assortment of kept items in so you don’t have to go upstairs juggling all the while.

After one last round of bureaucratic sign-in and card-showing you wander into the Reading Room at last. It’s smaller than the cathedralesque Bates Hall at the Boston Public Library, where you often go to write when you are home, and where you don’t need to crawl through wondrous tunnels and dodge chugging book trains to get a Book Driver’s License first. At the Boston Public Library you can just walk in off the street, anyone can, and sometimes anyone does, but the Reading Room is sacred, the Reading Room is Book Church and even those people who walk in off the street where they were yelling at voices only they can hear, even they are quiet in Book Church, there is a gravitas to the room that everyone recognizes, as it is here, at the Library of Congress, where the Reading Room is not long and rectangular and thoroughly lit by tall high windows facing out over Dartmouth Street, four stories up. The Main Reading Room of the Library of Congress is an octagonal space ringed in columns and arches of grey-veined golden marble, with bronze statues looming beneath halfmoon stained glass windows decorated with various shields — for the states, perhaps, you wonder? — and capped with a massive dome festooned with gilded rosettes reaching to a topmost circular mural identifying great civilizations of the past.

You don’t know what it all means; you haven’t researched it. It’s clear by now that this is not the relaxed workspace you expected and the air is thick with studiously academic silence. The desks are arranged in concentric circles radiating out from the center, all warm wood and inclined writing surfaces that nevertheless work well for laptops too and an individual brass lamp to go with every wooden chair and you’ll wonder, why did we ever stray from such a perfect assembly of pragmatism and gravity and angles for studying and writing? We probably wanted something more modern, more austere, to our own detriment. You will walk to one desk at the end of a row with thoughts of sitting there, but there is a coat on the chair; you will walk to another and set your things down and sit before realizing there is a laptop charger and several stacks of books marking this spot as also taken. You will move down one. Your neighbor will periodically return and leave; his stacks of books are all about historical ships.

You will cough loudly, unabashedly, just once, because you are getting over a cold, and you left those cough drops in your bag, and the sound will ring through the space with such suprising vigor and volume that you will struggle forcefully never to cough again.

Here in this space surrounded by older men who are probably faculty and young women who are probably students (or interns — one of those tunnels goes to the Capitol across the street) you will think about the machinations of government instead of writing the things you intended to write; you will wonder if, five years from now, ten years from now, your country will look anything like it does today, if progress is inexorable or if there is no good work that cannot be undone. You will think about all these buildings all over this city and the deep, pervading seriousness their forms evoke, the sense that here, at the seat of power, the most important work in all the world is being done, and yet if that’s the case then how could things have gone so awry, how could so many Americans think their best option for a brighter future was a professional charlatan. You understand it and you don’t; you think about your own long-term discomfort with the state of American politics, injustice, compromises, strategic decisions that result in people dying but no one really cares because it’s happening somewhere else to people who aren’t like you. You looked at the Capitol building as you walked here and felt vague disgust, not for the institution it represents but for the people who have so abused their offices and their responsibilities to serve their country and their consituencies in favor of deadlocked obstructionism and now, ultimately, a total abandonment of any principles to which they might once have held fast, because, you guess, power and money, money and power, this is all we’re about now.

In the midst of these thoughts, an elderly priest walks by, his collar peeking from the crew neck of an argyle sweater. You think about the human thirst for knowledge, of which spirituality has historically been an important part, and worry that it is being suffocated under this new ideology against learning and in favor of assuming you already know everything you need to know, that everything else is lies and propaganda (except for the actual lies and propaganda). Where do you go from here? Do you dare to hope? Do you give everything you’ve got to resist? What other choice do you have?

In the meantime, you are visiting the Library of Congress.