I am on the eleventh floor of a hundred-year-old hotel overlooking San Francisco’s Union Square through a webwork of painted-iron fire escape, and on the ground below, a man in dark clothes plays the trumpet.

The sound comes up between the buildings in swirls and flourishes, as though the air and distance between us exist only to refine and carry the tune. I will always stop when I hear a trumpet; I will involuntarily pause and forget everything else and listen. My grandfather played trumpet. My father did for a brief period too, but both he and I lack the nebulous something, the magic, the spark that born musicians have. Instead, we are born listeners.

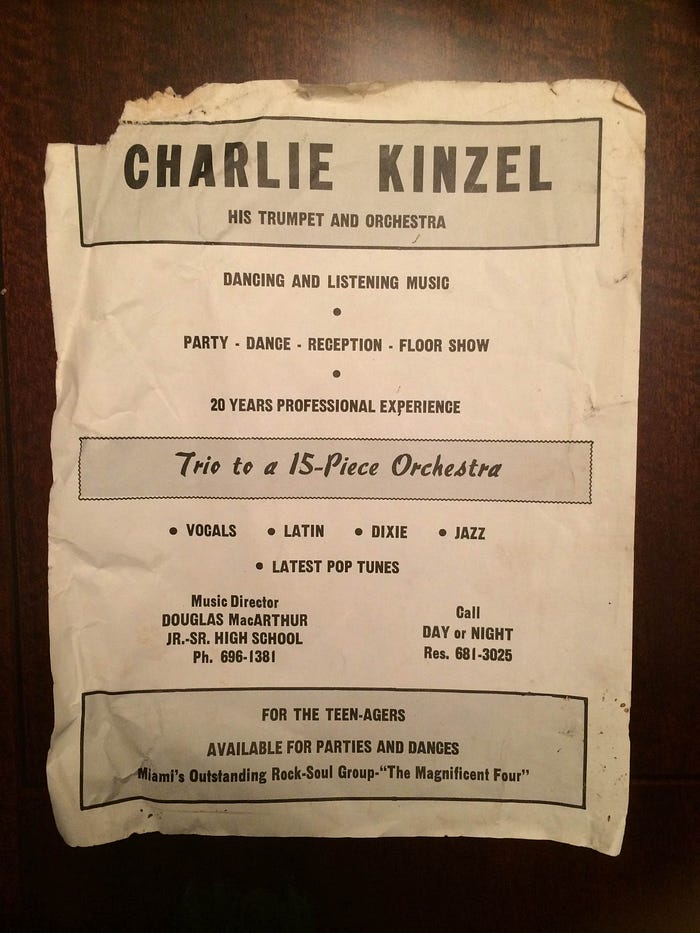

Charlie Kinzel played trumpet because it brought him joy — he did it his whole life, and when he had his second heart attack and my father went to see him in the hospital, all he wanted to know was if they’d gotten his horn out of the car. He had been driving when the heart attack happened, and he’d managed to pull into a Circle K parking lot to get assistance. His horn was left in the car, as he was busy with cardiac arrest. Could someone go get it and bring it to him?

The sound of a trumpet hits me in a place I can’t describe, I feel it in a visceral way, it draws warm filaments around my soul and holds it snug and secure. I’m standing at the open hotel window in a slipdress, leaning over the fire escape in what I am sure is a violation of hotel policy, but if I were slightly more certain that I could fly out over the square, carried on the music, I would be much further out than I am. Music, jazz, it gets inside me and I never, ever want it to stop, I have to fight to hold onto the moment gently and not crush it with needless worries that this will end, and what if I don’t remember it someday, what if it gets away from me like so much of my life already has, and I forget the time I leaned on a fire escape listening to variations on “When You’re Smiling” with strange tears springing to my eyes because that sound, that honeyed sound is somehow synced into my reptile brain, my DNA.

It’s taken me a long time to learn to see my life as a series of moments. An abusive and monstrous but also funny and kind former boyfriend of my mother’s used to refer to me as 13 going on 30. He said it not with a wry grin, like adults sometimes do, but with something like despair. I am a natural worrier. If something pleasant is happening, my first inclination is to think about how it is going to stop soon, and won’t that be sad. This constant thinking ahead stands in the way of my appreciating whatever the pleasant thing is in the moment that I have it, and so I must fight the urge to imagine the loss I will feel when it inevitably ends, so that I may feel it fully and accept the loss all the more readily later on. Because loss, understand, is as much of life as beauty is.

I don’t feel as though I ever really knew my grandfather. I knew the things he liked — he liked the trumpet, and his firepit, and playing horseshoes, and he liked building things, and teaching music, which he did, mostly in low income communities, for 45 years. A Julliard-trained musician, he loved jazz, and in all the visits to his house as a kid I remember seeing the television turned on exactly once, and finding that strange and unsettling. But there were records playing on the speakers he’d hardwired all through the house, all day long. I knew Dave Brubeck’s entire oeuvre long before I knew the man’s name.

He burned incense, he laid out snack platters of sliced Polish kielbasa and carrot sticks and called them “nibblins.” He made photo collages. He paid for my piano lessons for three years because he thought music education was so important, and I wonder if it ever disappointed him that I was never much good at it. I am fairly certain he would be proud to know I would eventually find work as a writer. But I can’t be sure. In my memory his eyes are bright but he is always an arm’s length away, his smile is vivid but the person he was is somehow obscured. It’s possible, you know, to grow up with a family member you know things about but don’t really know. A picture of a man holding a fish may tell you that man liked fishing, but it doesn’t tell you why. The man has to tell you. Failing that, you have to ask.

When my grandfather died, I was seventeen, and the day of his funeral I stood in the backyard of his magical house in the lake-speckled wilds of rural central Florida with headphones on, listening to Tori Amos’ “Yes, Anastasia” (“we’ll see how brave you are”) over and over again, because although I’d had the new album for weeks at that point I seemed never to have really heard that song before. I watched the birds at the bird feeders he’d set around the house; he also liked to feed the birds. That moment is still inside me like a photograph, and my mind’s eye still flips to that page in my memory every time I hear that song.

The things we remember often seem so random and purposeless; I can recall the half hour before a funeral twenty years ago with perfect clarity, and the sound of a trumpet can make me cry. But sometimes I try to remember the things I need most — what I am good at, what I am proud of, and the fact that I am not alone — and they seem to just slip away, intangible, uncertain, like reaching to catch smoke in my hand. They hide around corners and behind doors; I see a trailing tail or the hem of a coat and by the time I get there, it’s already gone.

The Union Square trumpet player takes long breaks between playing, standing still, the horn occasionally glinting under the streetlights. Without going back to the window, it’s hard to know if he has simply paused or has packed up and gone, and I hate to look because I don’t want to know, I’m happier living in this liminal space of waiting, in the hope that he may start to play again.

This originally appeared on Medium.